By Evan Louison & Brandon Harris

By Evan Louison & Brandon HarrisIt’s a truism, at least for most of us, that it is better to endure, through frailty and decline, than to check out early, slide out of life before we’ve wrung every minute we can out of it.

BAMCinematek's terrific program The Late Film, which runs through the 21st, speaks volumes about the contributions of senior citizens, in this case world class auteurs, once again reaffirming that there are charms to be had (and great film to be made) after you start collecting social security. As it's nom de guerre suggests, the series is a testament to the auteur’s swan song, to the late career death rattle, for many of the most celebrated (and nowhere near celebrated enough) authors of international cinema. The films included in this program are almost universally not considered their director’s finest work. In many cases the pictures are not the final film in the director’s career. Yet each provides fascinating insights into the ways a director can both change over the course of decades and how even the greatest moviemakers can never shake their greatests preoccupations and stylistic conceits.

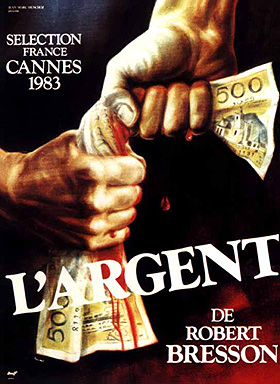

The great Calvinist Gallic auteur Robert Bresson's L'Argent shows a rebellious, iconoclastic defiance of gravity, a physical logic for demonstratively explicit puppetry with its props, makeup, and performers expressions and delicately followed movements. Capping a career in which he frequently referred to actors as models and refused the psychological insights of the popular modes of narrative filmmaking, Bresson (who even went so far as to claim that all filmmakers can and should be known as "cinematographers") goes yet further with L’Argent into uncharted of narrative territories. The film is turns maddening and terrifying, insightful and confusing.

Robert Altman's proudly plotless modern ballet chronicle The Company, designed as a vehicle for Neve Campbell, shows how effortless and graceful even Altman’s last movies, made when the maverick director’s wittiness had not receded with his lucidity, prove to be on repeat viewings. Some may find fault with much of his late career oeuvre, be it the poorly received southern intrigues Gingerbread Man and Cookie's Fortune or his Oscar nominated Gosford Park, (the first pair are as underrated as the later film is overesteemed), but like many of the director’s on display in this series, you sense an artist not quite at the height of his powers, but fully in tune with a style and series of preoccupations that have reached full maturity.

Stanley Kubrick’s posthumously released Eyes Wide Shut, ten years after its long awaited opening, still inspires the hesitancy and excitement it did in the summer of 1999, a puzzler who’s mysteries grow deeper as it ages. Many who were enthralled by films as varied as A Clockwork Orange, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, and The Killing, who contributed to the cult following that shaped Kubrick’s public persona, were immediately dismissive of the Bronx born director’s curious and often wonderful passion play. Adapted as loosely from Arthur Schnitzler's Traumnovelle as The Killing was from Clean Break and Dr. Strangelove was from Red Alert, the film is filled with a world that could only be the product of a mind still searching for clues to the big questions that envelop and consume relationships and our conception of sex and death. One may find reference to Kubrick’s plans to realize Schnitzler's work as far back as in interviews for Clockwork and there are moments contained within it, brought to dazzling life by through it lush and vibrant (and highly plasticized) sensuality that make one think this may have been the film he always wanted to make. Of course, Kubrick regretted the film before he died, confiding to friends that the critics “would eat him for lunch”. The notion, floated by some film academics, that he cast power couple Kidman and Cruise because of their lack of acting skills, as he apparently did when choosing Ryan O’Neal for Barry Lyndon, seems like a hollow appreciation of his delicate, obsessive craftsmanship; the images, the cuts, the choices with sound design and score, the brutal honesty somehow summoned from its world famous leads.

Scottish director Michael Powell, perhaps best known for his incendiary Peeping Tom, his marriage to Thelma Schoonmaker and his mentorship of Martin Scorsese, is included in the program with Age of Consent, a rather bold artifact from 1969 starring James Mason. The middle-aged/semi-innocent-sex-on-a-deserted-island-comedy was the product of the very close collaboration between Powell and his star James Mason immediately conjures a more well-known and celebrated picture featuring the lead performer, Kubrick’s Lolita. Here again we have Mason, not so long past the North by Northwest villainy days, chasing underage tail, though this time in a lazy, deluded sort of way. He plays a jaded abstract expressionist painter, who just happens to become, on retreat to a small Great Barrier Reef provincial isle, entangled with a young vacationer. Helen Mirren, in her screen debut, plays the young beachcomber who soon becomes Mason’s object of obsession. He goes on creepily to insist upon her modeling for him, and happens to come up against the most frustrating roadblock of only being able to paint her portrait perfectly and “accurately,” upon her disrobing. The picture ultimately doesn’t coalesce into anything meaningful or substantial, representing a mere whimper from the former enfant terrible of UK cinema.

The seeming ageless Portugese ageless master Manoel de Oliveira turns 101 this December, and after nearly 50 pictures, from silents and early talkies right up until our present digital age, shows no sign thus far of slowing or bowing in the least. His is a lurid and lonely cinema, as anyone who’s seem his 1987 gem Mon Cas can attest to. 2003’s A Talking Picture is by turns hysterical and mildly frustrating, bewildering and smirk inducing. One cannot in all honesty recommend it without erecting a rather unsteady criteria, especially when considering some of his other rather minimalist triumphs. De Oliveira’s cinema is unabashedly hyper-focused on verbatim historical facts, and the unfiltered, relentless insertion of such information into what would be otherwise plain and intellectually common conversations. It remains difficult to find any of his earlier magic touches herein; watching A Talking Picture is like being moored on an hour long international tour of the manmade wonders of the ancient world, represented mostly in static, half-hour, multi-lingual conversations from aging pillars of European art cinema and their mascot, the unintentionally hysterical John Malkovich.

The absurdity of this last mentioned film's abrupt, obtuse conclusion leaves one disquieted, but perhaps not quite as much as the finale of John Ford’s final picture, the rambunctious female missionaries in Asia adventure 7 Women. Plodding and occasionally beautiful, with a terrific, star making performance from Anne Bancroft, it recalls the great American master’s westerns in style and theme, recapitulating the dichotomies that inform his great pictures (Society versus Savagery, Spirit of the Law versus The Letter of the Law, the essential flimsiness of Manifest Destiny as a concept). Yet Ford seems lost here, as he was in such late career follies such as his last outing with Wayne, Donovan’s Reef, and his Civil Rights era black soldier faces discrimination pic Sgt. Rutledge. After a certain point in his career, he just wasn't making very interesting non-Western anymore. One often think of him solely in the context of the Westerns, but when you throw films as varied as The Informer, Young Mr. Lincoln, How Green was My Valley and The Grapes of Wrath, it becomes clear what range Ford showed over his 120 plus pictures. Yet as the 50s and 60s wore on, the further he got from Monument Valley and its familiar trapping and quarrels, the worse he films tended to be, with a few exceptions. 7 Women feels curiously detached from its South Asian setting and contains the simplified racial characterizations that marred Ford’s earliest Indian villains (they get more nuanced and ultimately ironic representations in his best Westerns, Fort Apache, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and The Searchers). Yet the closest he ever got to truly penetrating and working through the essential darkness of his protagonists was John Wayne’s virtuoso portrayal in The Searchers; he doesn’t take the leap with Bancroft’s rambunctious doctor, allowing her redemptive vengeance and a heroic death on top of her already mighty sacrifice for the other six women of the title.